Today I would like to make a new paper recommendation: Strengthening conceptual foundations: Analysing frameworks for ecosystem services and poverty alleviation research by Fisher J. A., Patenaude G., Meir P., Nightingale A. J., Rounsevell M. D.A., Williams M., Woodhouse, I.H. in Global Environmental Change (free access).

I will develop my recommendation from a two-fold perspective: first, the content of the paper and its contribution to knowledge and second, how I perceive it as a PhD student.

1) What does it say?

In this paper, Fisher et al. outline some of the various facets of ecosystem services frameworks and concepts that the research agenda on poverty alleviation could draw on. For nine conceptual frameworks, judged as “thinking-tools”, it provides a nice overview of relevant information including: definition and/or description of main elements, key authors, a diagram (if existent), the contribution to research on the nexus of ecosystem services and poverty, overlaps and/or possible linkages with other frameworks, critiques and weaknesses. Below are the nine frameworks and bodies of literature reviewed by Fisher et al., next to which I provide essential points gleaned from the paper:

The Sustainable Livelihoods framework (taken from Fisher et al. 2013), highlighted by the authors as one of the most holistic, and reflecting the complexity of rural development.

- Environmental Entitlements (Leach et al. 1999). With key notions such as “legitimate” versus “effective” entitlements, capabilities (Sen 1985), and categories of property rights (Schlager and Ostrom, 1992), it is the only framework that makes the distinction between access and availability explicit.

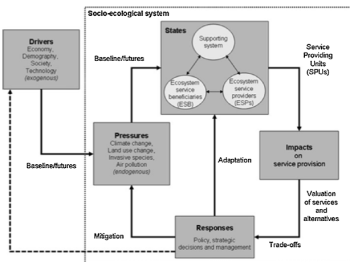

- Framework for Ecosystem Services Provision (Rounsevell et al. 2010). Based on the DPSIR chain, it recognizes the role played by beneficiaries in their interaction with ecosystem service, which creates potential for differentiation between social actors.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA 2005). Currently, the dominant ecosystem service framework and among the most advanced one in terms of categorization of ecosystem services and well-being components.

- Political Ecology (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987). With key focus on social justice and power, it is the strongest framework for analyzing access mechanisms and inequities in the distribution of ecosystem services.

- Resilience (Folke 2006, Holling 1973). Closely associated with the discourse on change, adaptive management, and unlinearity, it offers a conceptual basis for thinking about social-ecological systems.

- Sustainable Livelihoods (Chambers and Conway 1992, Scoones, 1998). Suited for the holistic analysis of poverty, it also offers various points of linkages (or insertion) for many frameworks with which it shares common elements.

- The Social Assessment of Protected Areas (linked to Sustainable Livelihoods) (Schreckenberg et al. 2010). Most comprehensive framework, but rather static by just enumerating elements that need to be considered by the research.

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB 2010). With a central focus on economic valuation, it emphasizes the distinction between ecological functions, ecosystem services, final ecosystem services, and benefits, in relation to human well-being.

- Vulnerability (Adger 2006, Fussel 2007). With key elements such as adaptive capacity, and social vulnerability, it is central for understanding poverty linked to the degradation of ecosystem services.

The paper also touched upon other topical debates and research questions that could facilitate the understanding of the linkages between ecosystem services and poverty alleviation:

- A broader definition of poverty in relation to well-being (unrestricted to material assets);

- The relationship between poverty and the environment, emphasizing on the vulnerability of the poor and their dependence on nature’s services;

- Which categories of ecosystem services contribute to which components of well-being and to which aspects of vulnerability?

- The constraints of access versus the constraints of availability of ecosystem services; which mechanisms govern access to which ecosystem services?

- Ecosystem services as “safety nets” against absolute poverty, rather than contributors to poverty reduction (i.e. increasing the standard of living above poverty line);

- The role of education, health and rural development in poverty alleviation.

The paper concludes by suggesting that a new conceptual framework for ecosystem services and poverty alleviation should comprise or try to tackle social differentiations (sensu Daw et al. 2011), power and political factors affecting access, control and distribution of the different categories of ecosystem services (in line with the framework of Environmental Entitlements and the body of literature around Political Ecology), and the dynamic relations within social-ecological systems (such as Framework for ecosystem service provision, the Resilience body of literature).

The framework for Ecosystem Service Provision (taken from Fisher et al. 2013), in the authors’ view one of the most dynamic frameworks due to its representation of a social-ecological system with directional relations and feedbacks.

2) Why do I like it?

Because when I first flicked through it, it was like Anthony Hopkins, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchet, Tom Hanks, Dustin Hoffman, Judi Dench and Emma Thompson and a couple of other giants I was not very familiar with, got together in a movie, including deleted scenes where they introduce themselves, their past roles and awards.

When you are a PhD student that comes across many frameworks and concepts (probably not so many as senior researchers, but enough to make things hard and confusing), it is really comforting and exciting to see them once in a while, compared, grouped, and reviewed according to a given criteria (here their achievements for the poverty alleviation research agenda). The novelty of this paper, as authors state in the methods section, is in the approach it takes, and in putting things into perspective, rather than in the content it delivers. In my opinion, this paper is more about laying one brick on the top of another than building another brick path. I find this much needed, especially at the beginning of one’s academic journey: to consolidate, link, compare concepts and then let them leaven.

This is not to say that having multiple frameworks per research question is negative. As Fisher et al. do point out in their example, each framework and body of literature has its own merits and suitabilities. However, a systematical categorization of those is more than welcome, especially for didactic purposes, and when novel research fields are emerging. I think the authors chose a propitious moment for this particular study, since conceptual work on poverty alleviation and ecosystem services is relatively in its early stages but emerging fast, with some notable recent contributions (Tallis et al. 2008, Daw et al. 2009). Such as systematization could be applied in the case of other conceptual frameworks as well, in order to help answer other established questions.

I would recommend this paper to academics who are involved in teaching and to PhD students. I see it as a useful pedagogical material, with different levels of complexity that allow switching between them (from definitions, descriptions to links and correlations). The list of references is also definitely worth mining. At the same time, the text is guiding the reader through topical and overly circulated notions that he/she could stumble repeatedly in many connected fields of research (e.g. capabilities, social justice, resilience, etc). Other pluses for students are that it is very accessible in terms of language and flow, and has a predictable structure that makes it easy to navigate between the frameworks’ strengths and weakness.

Photo credits: http://www.huffingtonpost.com

To my mind, PhD students are not primarily in search of novelty, but strive instead to acquire some conceptual foundations and be able to operate with those. Finding all these frameworks (that you read so many things about) in one place, with each being influential in its own field, makes you feel the world makes more sense. It gives more consistency to your subject of research* and brings a sense of limpidity, just as if all frameworks come together in a conceptual orchestration, where each one would play its part.

*My last field study was on the distribution of ecosystem services within the population of Southern Transylvania.

Selective bibliography

Adger, W.N., 2006. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16, 268–281.

Blaikie, P.M., Brookfield, H.C., 1987. Land Degradation and Society. Routledge, London.

Chambers, R., Conway, G., 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296.

Daw, T., Brown, K., Rosendo, S., Pomeroy, R., 2011. Applying the ecosystem services concept to poverty alleviation: the need to disaggregate human well-being. Environmental Conservation 38, 370–379.

Folke, C., 2006. Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change 16, 253–267.

Leach, M., Mearns, R., Scoones, I., 1999. Environmental entitlements: dynamics and institutions in community-based natural resource management. World Development 27, 225–247.

Rounsevell, M., Dawson, T., Harrison, P., 2010. A conceptual framework to assess the effects of environmental change on ecosystem services. Biodiversity and Con- servation 19, 2823–2842.

Tallis, H., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M., Chang, A., 2008. An ecosystem services framework to support both practical conservation and economic development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 28, 9457–64.